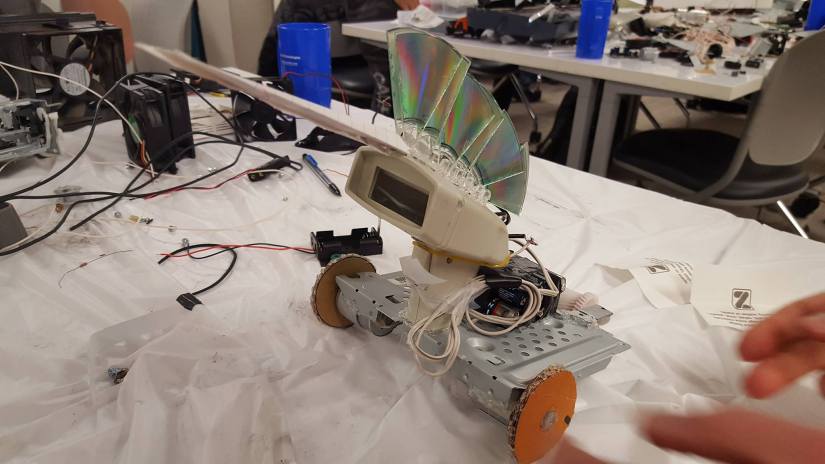

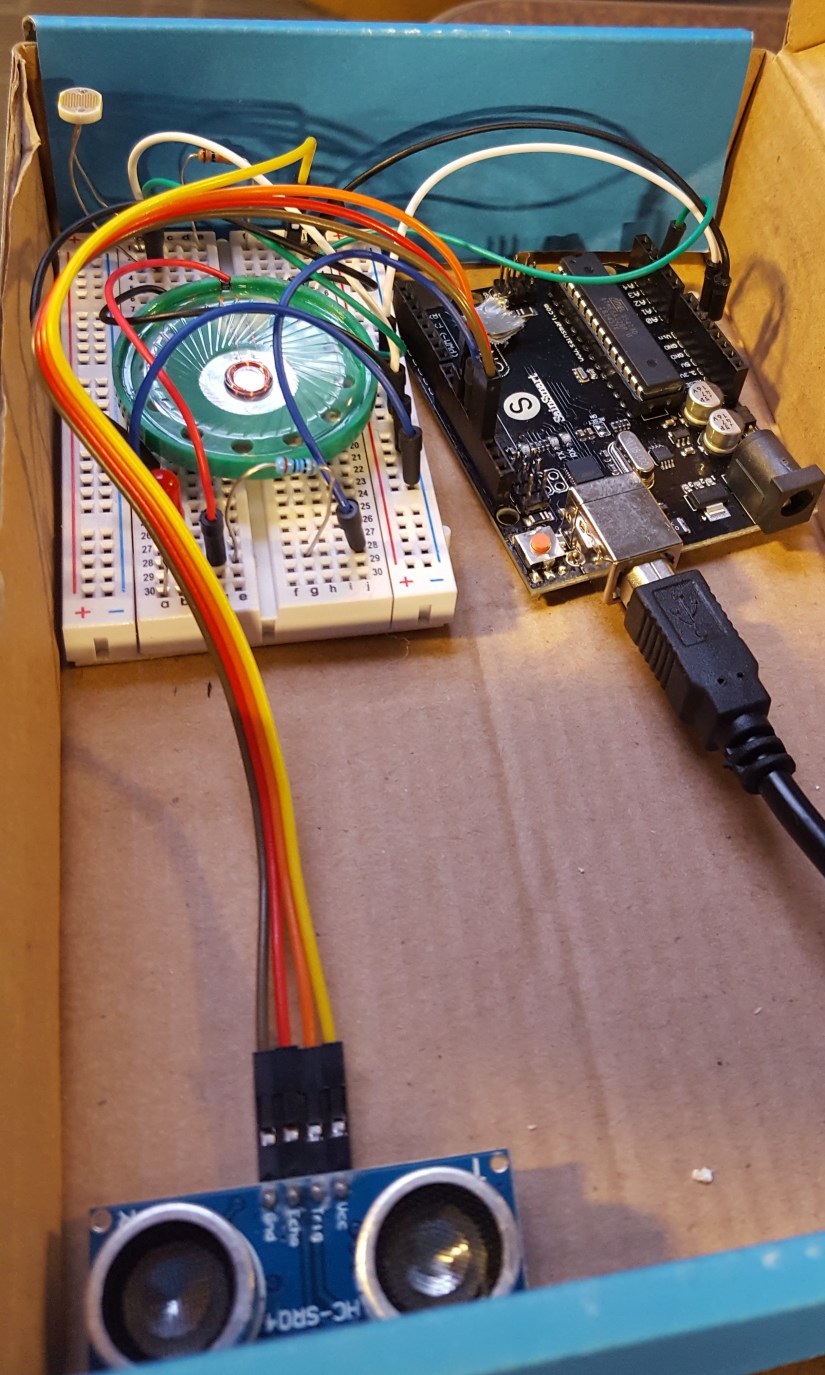

This semester I worked with Violeta Flores to develop a modular security system for our ECE outreach group at Colorado State University. This is one of many projects made to show various applications of mathematics, engineering concepts, and effective design for high school aged kids. For this project we placed it in a box (and did tests on doors) so that when the box is opened the device blares a whooping and whining alarm. While you can make more robust systems, this project was mainly geared towards introducing electrically based sensors to make those concepts more digestible for beginners.

Originally we wanted to make it send a text or email log and alert, but in the limited time we were unable to implement it due to network security issues. What we were able to ensure the removal of any one sensor does not affect the security system, and the presence of other sensors do not impact another’s ability to perform. This corresponds to the “modular” nature of the device. The alarms were set differently so that you could tell which sensor reading was triggering the alarm.

You can show these sensors, invite questions, and ask for suggestions on how to improve the circuits capabilities or resiliency to attacks with students. Exploring this can begin a journey into the deep wealth of possibilities in Electrical Engineering. This also starts a conversation about some of the modern problems we face with IoT, cyber warfare, and makes an emphasis on the many different design perspectives in ECE. One could spice up an event by placing a $5 bill and challenging students to retrieve it without setting off the alarm. The overall circuit (Fig 1) costs about $25 to make, though you could make it for ~$10 using simpler circuitry. Additionally the removal of any one sensor does not affect the security system, and the presence of other sensors do not impact another’s ability to perform.

I largely just had fun learning about all the different sensor types and how each sensor actually works in a more physical way rather than just the code, as typical for an arduino project. A majority of the time spent on this project was researching the different sensors and writing lesson plans to demonstrate the ones we ultimately choose to use. I look forward to expanding this project to more complicated examples, and specifically hope to make models of the US electrical grid to more personally explain its current security issues.

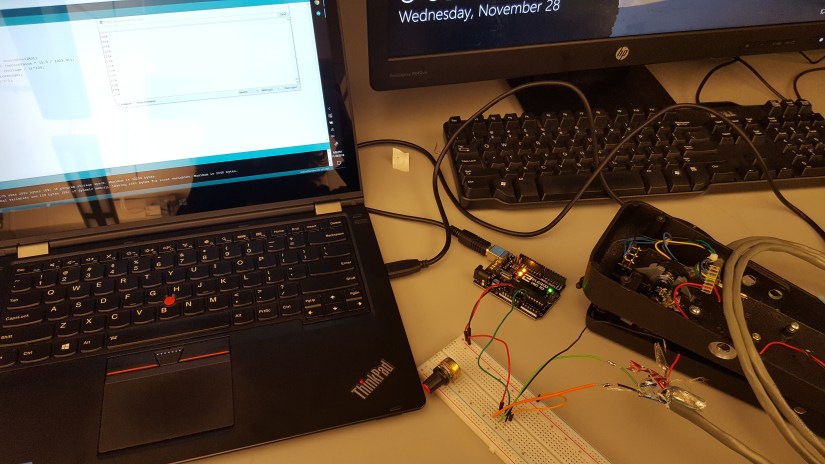

Fig 1: Overall circuit

Sensors

Photoresistor: A photoresistor (PR) works by taking in photons from light and exciting the electrons (Fig. 1) in Cadmium Sulfide semiconductor (CdS track) zigzagging in the middle. The CdS track is surrounded by two electrodes. The more light that is present, the more electrons are allowed to “jump” over to the other electrodes and their terminals, this reduces the resistance in the PR component. When it is dark, the PR will be at its highest resistance level due to the electrons staying in place. When the PR is exposed to maximum light, the electrons will make the lowest resistance but always maintain some amount of resistance.

Photoresistors are commonly used in city street lights as it allows the lights to be operated efficiently without the need for expensive remote on/off capabilities. A PR was used in this circuit as a cheap way to detect and build your first security device, while also leaving room to show how various security vulnerabilities need to be accounted for.

Within the circuit we built, the PR is placed in a voltage divider (Fig 2) circuit so that as the resistance varies in the PR, a more intelligible voltage change can be detected in the arduino.

Fig 2

Fig 2

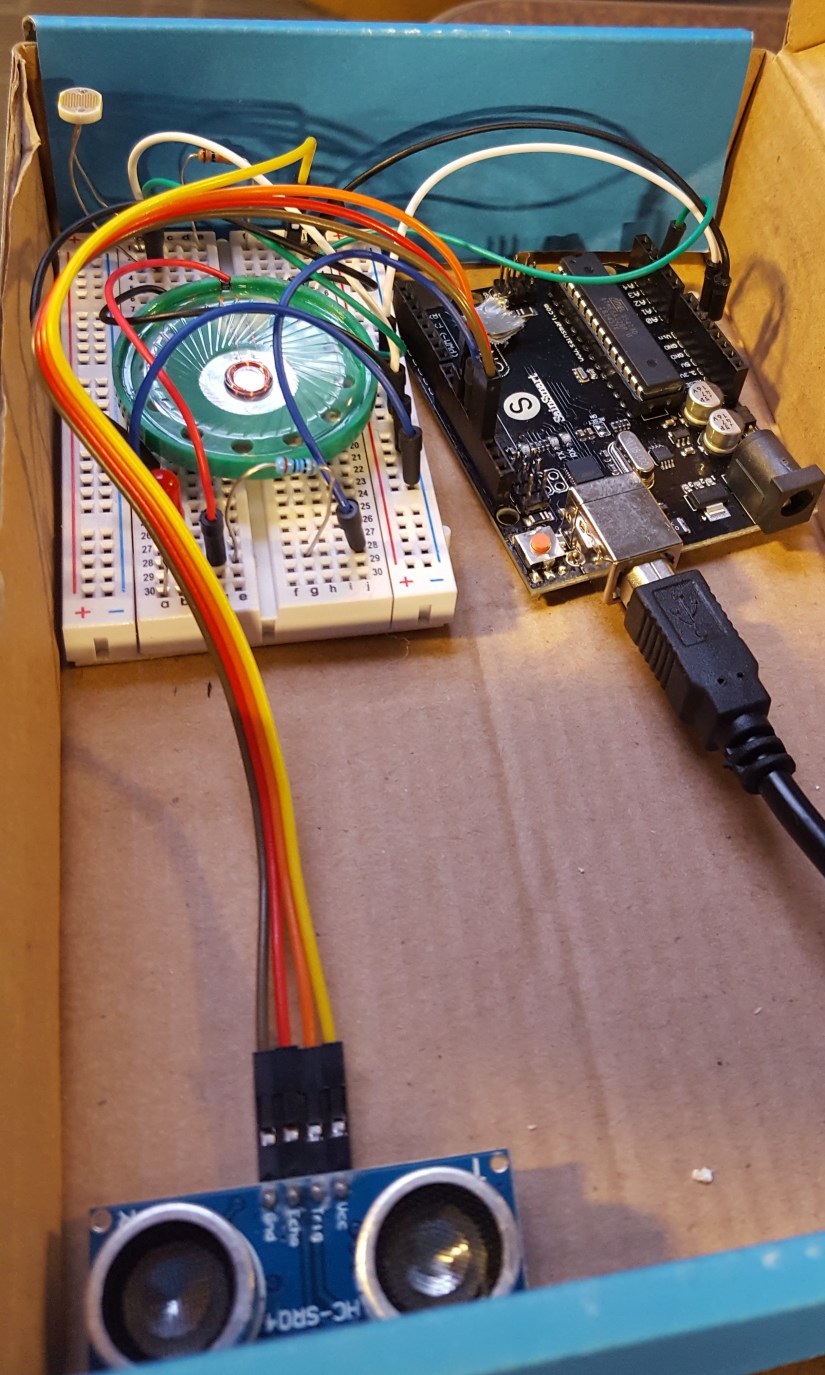

Sonic sensor: Arduino sonic sensors work by emitting sound from its sensor area and waits for a return. If the sonic sensor receives an echo signal similar to the one it output, it outputs a sound at 40000 Hz (Fig 4). The sound then bounces back if and when it hits another object. That signal is then read and a specific distance can be determined to locate the obstacle.

For this project I used a HC-SR04 Ultrasonic Module. This specific sonic sensor module has 4 pins: Ground, common Voltage [connected to a 5 volt pin], trigger, and echo [both connected to basic I/O pins].

The trigger should be set to a high state at 10 µs. This causes there to be 6 cycles of sonic bursts that will be received in the echo pin. The echo pin tells us the time the wave traveled in microseconds. This is achieved by code below and setting alarm trigger for 3.4cm [or whatever you want the distance to be].

duration = pulseIn(echoPin, HIGH);

distance = (duration / 2) * 0.0344;

Fig 3

Fig 3

Fig 4

Fig 4

Contact sensor: The direct contact sensor [simply made of two wires] is the cheapest and easiest to implement, though also probably the most vulnerable of all the sensors. The contact sensor essentially just makes a short in the circuit following the photoresistor, triggering the same light based alarm [whoop]. For this project I made a twisting of the two wires so that there were multiple points of contact, and harder to fault. This springy quality also helps the sensor last a longer period of time, allowing it to bounce back into shape/position after the container is closed again.

References

fritzing.org Fig 1

robotplatform.com Fig 2

hostmath.com Fig 2

howtomechatronics.com Fig 3

https://cdn2.bjultrasonic.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Ultrasonic-Sensors.jpg Fig 4

circuitbasics.com Help with sonic code

Bibliography

How to setup sonic ranger, https://howtomechatronics.com/tutorials/arduino/ultrasonic-sensor-hc-sr04/

“Tone” Arduino, www.arduino.cc/reference/en/language/functions/advanced-io/tone/

Fig 2

Fig 2 Fig 3

Fig 3 Fig 4

Fig 4